CNN —

Brazil votes for a new president on Sunday, in the final round of a polarizing election that has been described as the most important in the country’s democratic history.

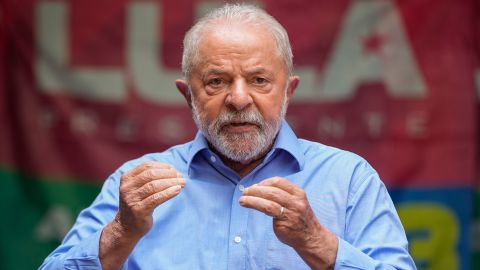

The choice is between two starkly different candidates – the leftist former president Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, popularly known as Lula, and the far-right incumbent Jair Bolsonaro – while the country struggles with high inflation, limited growth and rising poverty.

Rising anger has overshadowed the poll as both men have used their massive clout, on-and-offline, to attack each other at every turn. Clashes among their supporters have left many voters feeling fearful of what is yet to come.

The race could be a close one. Neither gained over 50% in a first round vote earlier this month, forcing the two leading candidates into this Sunday’s run-off vote.

Lula da Silva was president for two terms, from 2003 to 2006 and 2007 to 2011, where he led the country through a commodities boom that helped fund huge social welfare programs and lifted millions out of poverty.

The charismatic politician is known for his dramatic backstory: He didn’t learn to read until he was 10, left school after fifth grade to work full-time, and went on to lead worker strikes which defied the military regime in 1970s. He co-founded the Workers’ Party (PT), that became Brazil’s main left-wing political force.

Lula da Silva left office with a 90% approval rating – a record tarnished however by Brazil’s largest corruption probe, dubbed “Operation Car Wash,” which led to charges against hundreds of high-ranking politicians and businesspeople across Latin America. He was convicted for corruption and money laundering in 2017, but a court threw out his conviction in March 2021, clearing the way for his political rebound “in a plot twist worthy of one of the Brazilian beloved telenovelas,” Bruna Santos, a senior advisor at the Wilson Institute’s Brazil Center, told CNN.

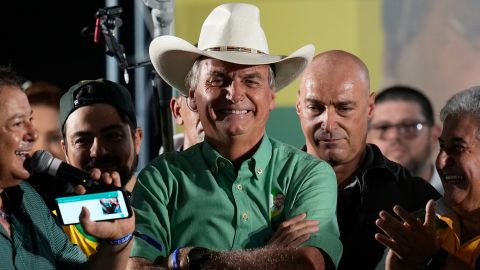

His rival, Bolsonaro, is a former army captain who was a federal deputy for 27 years. Bolsonaro was considered a marginal figure in politics during much of this time before emerging in the mid-2010s as the figurehead of a more radically right-wing movement, which perceived the PT as its main enemy.

He ran for President in 2018 with the conservative Liberal Party, campaigning as a political outsider and anti-corruption candidate, and gaining the moniker ‘Trump of the Tropics.’ A divisive figure, Bolsonaro has become known for his bombastic statements and conservative agenda, which is supported by important evangelical leaders in the country.

But poverty has grown during his time as President, and his popularity levels took a hit over his handling of the pandemic, which he dismissed as the “little flu,” before the virus killed more than 680,000 people in the country.

Bolsonaro’s government has become known for its support of ruthless exploitation of land in the Amazon, leading to record deforestation figures. Environmentalists have warned that the future of the rainforest could be at stake in this election.

The race is a tight one for the two household names who espouse radically different paths to prosperity.

Bolsonaro’s campaign is a continuation of his conservative, pro-business agenda. Bolsonaro has promised to increase mining, privatize public companies and generate more sustainable energy to bring down energy prices. But he has also has vowed to continue paying a R$600 (roughly US$110) monthly benefit for low-income households known as Auxilio Brasil, without clearly defining how it will be paid for.

Bolsonaro accelerated those financial aid payments this month, a move seen by critics as politically motivated. “As the election loomed, his government has made direct payments to working-class and poor voters – in a classic populist move,” Santos told CNN.

Bolsonaro’s socially conservative messaging, which includes railing against political correctness and promotion of traditional gender roles, has effectively rallied his base of Brazilian conservative voters, she also said.

Lula da Silva’s policy agenda has been light on the details, focusing largely on promises to improve Brazilians fortunes based on past achievements, say analysts.

He wants to put the state back at the heart of economic policy making and government spending, promising a new tax regime that will allow for higher public spending. He has vowed to end hunger in the country, which has returned during the Bolsonaro government. Lula da Silva also promises to work to reduce carbon emissions and deforestation in the Amazon.

But Santos warns that he’ll face an uphill battle: “With a fragile fiscal scenario (in Brazil) and little power over the budget, it won’t be easy.”

Lula da Silva faces a hostile congress if he becomes president. Congressional elections on October 3 gave Bolsonaro’s allies the most seats in both houses: Bolsonaro’s right-wing Liberal Party increased its seats to 99 in the lower house, and parties allied with him now control half the chamber, Reuters reports.

“Lula seems to ignore the necessary search for new engines of growth because the state cannot grow more,” she said.

A Datafolha poll released last Wednesday showed 49% of respondents said they would vote for Lula da Silva and 45% would go for Bolsonaro, who gained a percentage point from a poll by the same institute a week ago.

But Bolsonaro fared better than expected in the October 2 first round vote, denying Lula da Silva the outright majority which polls had predicted. The incumbent’s outperformance of the polls in the first round suggests wider support for Bolsonaro’s populist brand of conservatism, and analysts expect the difference in Sunday’s vote to be much tighter than expected.

There could be any number of other surprises. Fears of violence have haunted this election, with several violent and sometimes fatal clashes between Bolsonaro and Lula da Silva supporters recorded in recent months. From the start of this year until the first round of voting, the US non-profit Armed Conflict Location & Event Data Project (ACLED) recorded “36 instances of political violence involving party representatives and supporters across the country,” that suggests “even greater tensions and polarization than recorded in the previous general elections.”

Critics also fear Bolsonaro has been laying the groundwork to contest the election. Though he insists he will respect the results if they are “clean and transparent,” Bolsonaro has repeatedly claimed that Brazil’s electronic ballot system is susceptible to fraud – an entirely unfounded allegation that has drawn comparisons to the false election claims of former US President Donald Trump. There is no record of fraud in Brazilian electronic ballots since they began in 1996, and experts are worried the rhetoric will lead to outbreaks of violence if Lula da Silva wins.

“In this consequential election, the confidence we have in the strength of Brazilian democratic institutions is going to be challenged,” Santos said.

English (US) ·

English (US) ·